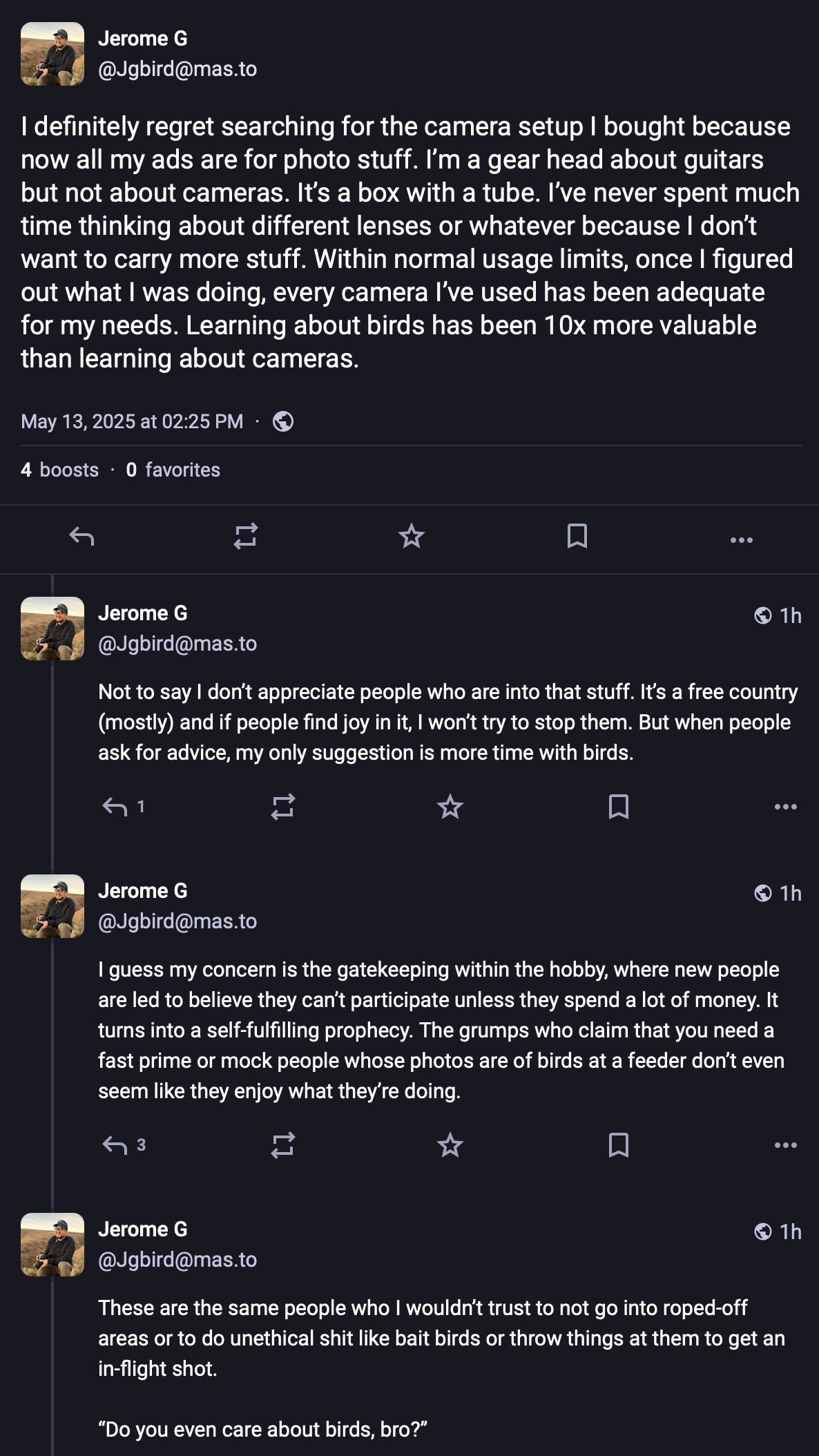

Gatekeeping

(inspired by a wise Mastodon thread)

It made me think that a lot of people’s real hobby is gatekeeping, but they apply it to different avocations.

Way back in the ’90s I was a member of a photography club. Each month, there would be a competition among members. Pictures were scored from 1-5 on each of three criteria, which were something like technical expertise, aesthetics, and realization of the month’s theme. Everything was highly formalized with rules. Entries could only be recent slides, must comply with very specific labelling requirements, and so on, but the rules didn’t end there. Interpretation of the theme had to be extremely literal. I was lectured about frivolity on more than one occasion when using the theme metaphorically.

In the technical category, there were also a lot of absolutes. Visible grain in an image at normal magnification was an immediate disqualification. Technical points were deducted if there was anything remotely out of focus. Portraits which were allowed to have bokeh — but only if you couldn’t determine how many blades the lens diaphragm had. Furthermore, it was considered a technical flaw to have a portrait where the subject’s nose broke the outline of their face or had more than one reflected light visible in each eye. It wasn’t considered good form to mention make of the camera during the competition itself, but everybody knew who shot Leicas or had Zeiss lenses on their Nikons, and this influenced technical scores accordingly.

But beyond these kinds of rules, one of the old-timers had developed a set of “aesthetic guidelines” which were ruthlessly applied (in retrospect, these may have been born of some form of OCD). Two points would be subtracted from any image’s aesthetic score if there was water breaking the bottom of the frame “because that’s bad composition.” Any image that was brighter near the bottom than the top lost points. Landscapes that were not black and white had to have a person or a horse visible “to create interest.” Pictures of urban or industrial scenes had to be taken in hard daylight, while pictures of nature would lose points for not being taken at the Golden Hour. Pictures of people had to have an even number of eyes visible. Lines always had to lead into the image and never out.

I remember on one occasion, two of the judges arguing about a picture’s aesthetic qualities and one finally taking out a tape measure to confirm that the eye of a seabird was not exactly 33% from two edges of the frame. He triumphantly reduced the picture’s score for violating the “rule of thirds.”

I tried to participate on their terms for a lot longer than I should have. I was routinely chastised for not taking photography seriously because I didn’t study up on the rules. Needless to say, I eventually quit. I’d lost a lot of enthusiasm for photography, and it took a long time to get excited about it again.

I see this as a common thing in “typical guy hobbies” be they photography, cars, phones, motorcycles, programming languages, computers, guitars, knives, operating systems, guns, bicycles, or gaming systems. It often manifests as confusing the gear with the hobby, but also devolves into arguments about X being better than Y. It turns out that arguing in-group / out-group status is more interesting for a lot of folks than the hobby they’re ostensibly enjoying.

“Forget that stuff,” I yell (trying to convince myself and everyone else). Go out and do the thing, use what you’ve got, and enjoy it. That’s the real point, after all.